Excerpt from Boat Girl

Seashell

George Town, Bahamas, Winter 1986

Age 6

There were three main beaches in George Town: Volleyball Beach, on the west side of Stocking Island, Hamburger Beach, named for a little burger shack run by the Peace and Plenty Hotel, and the Ocean Beach on the Exuma Sound side of Stocking Island, facing east. The Ocean Beach was about a mile and a half long, with patches of reef where the ocean broke in foamy waves.

The cruising mothers took their dinghies to one beach or another with their kids almost every afternoon so they could body surf or swim or build sand forts and bomb each other with sand balls. I guess we were making up for the lack of social company that we experienced in other places. The mothers, for the most part, were just happy to escape their husbands and the tight confines of life aboard a boat for a few hours. We'd visited George Town the year before, and it, either by chance or by our parents' choice, became our place to socialize.

|

| Chez Nous at anchor in the Bahamas |

For a month or so out of every year, George Town meant social structureplanned activities such as the Annual Cruising Regatta, weekly potlucks on the beach, afternoon volleyball. For that, my dad resented it. Social structure was what he had taken his family cruising to avoid. And the social structure that was there, he said, wasn't the healthy kind. It was the kind where people did whatever they wanted, partying all day and drinking at noon rather than waiting until a respectable hour like six o'clock. It was the kind of social structure, he said, where adults acted like kids, forgetting responsibilities such as taking care of their boats and finding ways to make money. The other kids were fun to be around, but I didn't like any of them that much. They were all more athletic than I was, and they wanted to play games that involved running. I was happier sitting alone and thinking, making up elaborate stories about characters I'd created.

The day I met Michelle, I was wandering Ocean Beach, lost in my own head, singing one of the only songs I knew from my parents' collection of cassette tapes. It was Jimmy Buffett's Son of a Son of a Sailor. I couldn't remember all the words, so I made them up as I went.

A flurry of motion coming from the sand dunes interrupted my singing. I couldn't tell what it was at first, because the sea oats were thick and tangled at the edge of the beach, and the movement was just behind them. Then a wall of sand sprayed out like a boat wake, and a girl about my age tumbled down the dune, rolling over and then somehow landing on her feet right next to me. Her skin was the same color as the sea oats, and she had a sunburned nose and bright green eyes and a mess of black hair.

I know that song! she said. Her voice was squeaky, and didn't seem to quite fit her body. She pushed the mop of hair away from her eyes and blinked at me, like it was amazing that we both knew the same song. Lots of parents listened to Jimmy Buffett, especially parents who lived on boats, but somehow this was different.

We sang it together, pulling the words out of our new collective memory, and became inseparable.

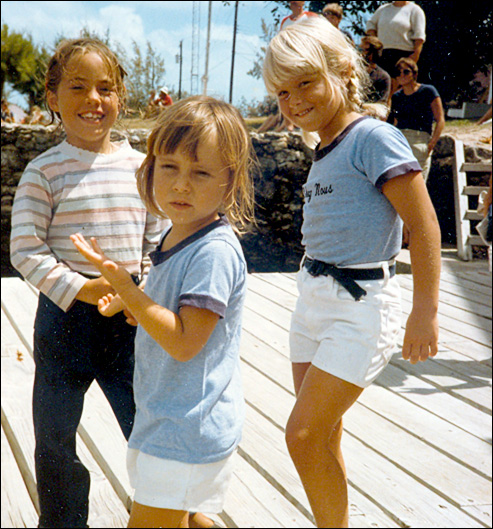

|

Melanie, Carolyn and Michelle examine conch

at the Cruising Regatta in George Town, Bahamas, in 1986 |

Michelle was grown-up at six. She and her father, Gary, lived aboard a 30-foot O'Day sloop called Indian Summer . It was close to being the smallest boat in George Town. Her mother had cruised with them for awhile, but at that point she had moved off the boat and was spending all her time back in Michigan. (I don't know when their divorce was actually finalized.) Gary ran an auto repair shop back on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. During the summers he bought, fixed and sold junk cars, and a buddy of his ran the shop during the winters so that Gary could sail. I was jealous of the things he let Michelle do.

She had her own rowing dinghy, and there was talk that she might even get an outboard motor for it. She rowed it and sailed it around the anchorages off of Stocking Island all by herself. My parents were more cautious. They wouldn't let me take our rowing dinghy out by myself. They wanted to be sure that I knew how to row, so they tied the dingy off the stern of Chez Nous and had me row back and forth behind the boat. It's how I learned to row, my dad said. What if you got caught in the current and couldn't get back? You'd wish you were tied to the boat. This was typical, overly-cautious, worst-case-scenario Dad.

Michelle sailed circles around Chez Nous in her dinghy. She came over to tease me, telling me how dumb I looked wearing my life jacket, sitting in a tethered rowboat.

One day, I was rowing as hard as I could against the tether, trying to see if I could make the big boat move, pretending to be a tugboat captain. Michelle rowed over to me in her dinghy. We're going to town, she said. My dad wants to take you with us.

My parents leaned over the lifelines of Chez Nous , worried.

When will you be back? Dad asked. I don't know. Before sunset, Michelle said. We just need to get some fuel and water and food and stuff. He said he'd buy us burgers at Frida's.

Oh no, Mom said. My family had a rule against buying burgers anywhere in town, because the burgers were cooked on outdoor grills and were supposedly encrusted with flies. Dad told us they were made of goat meat, and he always made sure to point out that the local goat population was a little smaller each time we made a trip to town.

|

| Melanie, Carolyn and Michelle in George Town, Bahamas, in 1986 |

Dad went over in the big dinghy to talk to Gary, I guess to make sure the boat wasn't about to sink and to give Gary some lunch money for me. Dad probably interrogated Gary, threatened him, or at least shook him up a little, but Gary never let on. Michelle and I climbed aboard Chez Nous so I could change clothes and grab an extra life jacket.

Carolyn threw a tantrum because she wasn't allowed to go. She screamed and tried to bite me, but I managed to push her off. Her teeth were sharp like a puppy's, and they scraped my arm. She took a fistful of her sun-streaked brown hair and pulled it out, still screaming. I hate you, she said, throwing the hair at us. I'm not sure whether it was directed at Michelle or me. Why can't I go? Mom held her by the elbow and said, You can do things with your friends too, and Melanie doesn't have to go with you. She guided Carolyn off to draw pictures at the salon table.

Indian Summer was much smaller than Chez Nous, and the small engine under the cockpit rattled the whole boat. I knew Gary would rather have sailed the mile across Elizabeth Harbor to Georgetown, but there was no wind. He made sure the companionway hatch was open so Michelle and I had plenty of fresh air while the engine sputtered exhaust into the cabin. We sat on the floor, where Michelle crafted a friendship bracelet out of blue and purple embroidery floss. I wanted some pink in it too, but she insisted that pink wasn't my color. When she tied the bracelet around my ankle, I thought it was the prettiest piece of jewelry I'd ever seen. I swore I'd never take it off.

Dad, Michelle called up the companionway, can we listen to Jimmy Buffett?

You know how to work the tape player, Gary said. He was intent on navigating the boat safely across the harbor, and he only took his eyes off the water long enough to look down at us and smile, a smile I learned he only reserved for his daughter. I learned a lot of things about Michelle's family over the next fifteen years.

When Gary worked in the auto shop during the summers, he took Michelle in with him and let her crawl around among the mechanics and tools and grease. The mechanics called her Bondo Baby, because she always got herself covered with the thick putty used in auto body repair. Michelle's mom, Kathy, was beautiful and wispy, and, while I believe that she and Gary never fell out of love with each other, their divorce was ugly. It was never clear to me whether Gary or Kathy had legal custody of Michelle.

|

| Jimmy Buffet - Songs You Know by Heart, |

We listened to Buffett's Songs You Know by Heart, and it was the first time I heard Why Don't We Get Drunk and Screw, a song that my parents had dubbed over on our own copy of the tape. I thought it was odd that our tape was missing the track, but didn't think the song was that great. It didn't make a whole of sense.

Michelle and I screamed along with Son of a Son of a Sailor, and, even though Gary laughed at us, I think he was secretly thrilled. Over in George Town, Gary docked the boat at Exuma Services, the town's only marina. Michelle and I spilled off the boat and ran down the dock without our shoes, Gary yelling something to us about not getting splinters.

Michelle found a group of Bahamian kids who were out of school on their lunch break, running around in their starched uniforms. They chased the scrawny chickens that darted under our feet. My parents never gave Carolyn and me a chance to play with the Bahamian kids. Trips into George Town with my parents were usually all business.

Gary was the opposite of my dad. Dad was careful and conscientious. He dressed up to go to town, made sure to shake hands with the right people, and carried a soft briefcase whenever he went to Batelco, the Bahamian phone company. The Batelco office was the only place on the island where you could make and receive phone calls to and from the States. Gary wore cut-off jeans and didn't mind showing off his beer gut. He laughed a lot more than my dad did, and he knew different types of people.

Gary ordered for us at Frida's. We sat at a long picnic table and watched as the burgers sizzled over the open grill. I tried to find the goats, and Gary pointed to where they were tied next to a small pink house. I'd have to tell my dad that the goats were alive and well.

The burgers here are so good because they come from Venezuela, Gary told us. And, you have to get everything on them. He left the table and went over to the grill, pulled some wet five-dollar bills from his pocket, and turned his back to us so we couldn't see what he was putting on the burgers. The smell of beef and charcoal and burnt drippings wrapped around Gary's big body and drifted across the dry grass and sand burrs to our table. Michelle swatted a fly with her hand and wiped it off on the bench, leaving a black smear.

You just wait, she said. This will be the best burger you've ever had. My stomach rolled over a couple of times.

When Gary turned around, we saw three paper plates stacked with burgers that might as well have reached the clouds. The top of each bun was sliding off because there was so much stuff piled underneath. Mayo on the bottom, then the burger, then cheese, ketchup, pickles, onions, lettuce, tomato, and mayo and mustard on the top. And here's more ketchup, Gary said. He set the plates down in front of us.

I could barely get my hands around my burger. Michelle's hands were the same size as mine, but she ate hers like a pro, ketchup dribbling down her chin, lettuce falling all over her lap and the table. Gary finished his in about two bites. When I finally managed to get mine into my mouth, I knew what hamburgers were supposed to taste like. It was well done, because all of us knew better than to eat rare burgers in the Bahamian Out Islands, but it wasn't the cardboard patty that you usually associate with well-done burgers. It was perfect.

Michelle and I followed Gary around town, the three of us singing. I loved the fact that Michelle and her dad didn't think there was anything strange about singing in public. As we climbed back aboard Indian Summer for the trip back across the harbor, still full from the burgers, Gary said, Jimmy Buffett, eat your heart out! This is the life.

|

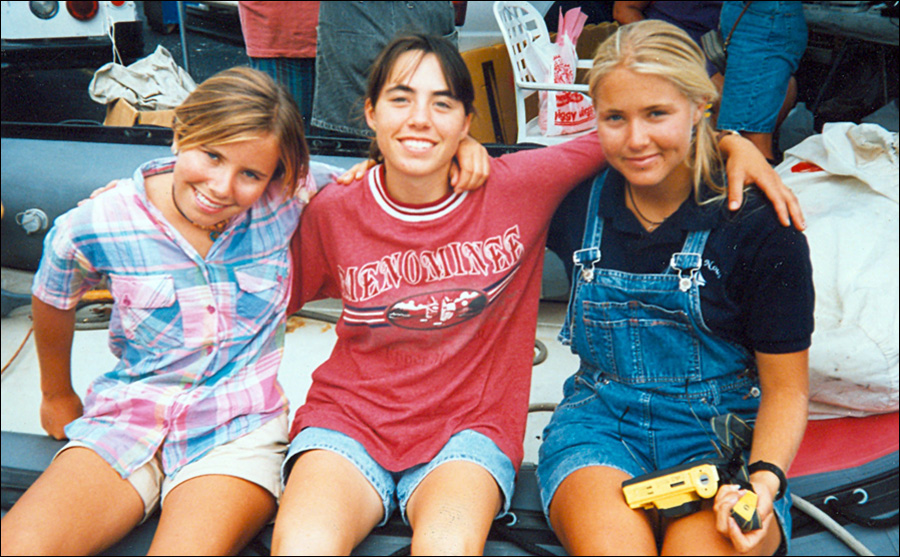

| Melanie, Carolyn and Michelle sitting on Michelle's dinghy at the Dania Flea Market in 1995 |

|